|

|

||

|

Home | Introduction | Contents| Feedback | Map | Sources | Glossary |

||

|

16

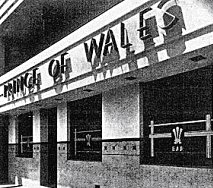

Prince of Wales Hotel

A

Prince of Wales Hotel was built on this site in the nineteenth century. It was

an unpretentious drinking pub and demolished in 1936. The present stylish

Prince represented a dramatic change in direction. It was designed by the

prolific hotel architect Robert H. McIntyre and completed in 1937. Hansen &

Yuncken were the builders. McIntyre was the father

of Peter McIntyre, Emeritus Professor of Architecture at the

It had four swish stories with projecting balconies over a square plan, with

aerodynamic horizontal lines and its name lettered in steel ribbon. At left,

the residential entrance was faced with black (Vitrolite)

It is said that from the start it successfully attracted a young, stylish clientele, the smart set, for almost twenty years. ‘Nothing was spared in the way of comfort and convenience’. For the hotel, this represented a shift away from concentrating on the bar trade, to attract dining and residential clientele, with function rooms and comfortable lounges with fireplaces and leather armchairs over two levels and ‘carpets on all the floors’.

In January 1936 King George V died and was succeeded as king by his son, the

Prince of Wales who became Edward VIII. Edward’s reign lasted less than a year,

until the Empire held its breath as he abdicated, under a black cloud, in order

to marry his lover, Mrs Wallis Simpson. They became

the Duke and Duchess of

It is extremely odd that the name ‘Prince of Wales’ should be perpetuated in the

new, glamorous hotel, just as the sorry tragedy of that other Prince of Wales,

inexorably unfolded. I hope that the reason was sheer Australian

bloody-mindedness towards

Prince of Wales Hotel, 1997

The etched glass windows at first floor level include the triple feathers

emblem, similar to the fleur-de-lis, of the Prince of Wales. They were

the earliest known designs by the eminent Australian theatre designer, Loudon

Sainthill (1919-69), immediately after his (and

only) education at the

Details of Prince of Wales Hotel

The Prince of Wales was used as a headquarters for the

There were no major alterations to the building until the 1960s, when all the bedrooms were modernised and a small sympathetic addition made at the rear. In the 1970s, further major alterations were made. A large multi-storey carpark was erected at the rear of the hotel, facing Jackson Street and a supermarket in the basement, shops and arcade were inserted off Acland Street, with a large function room at first floor (the former dining room?), accessible from the Fitzroy Street entrance. This became known as the Band Room. The first floor balcony was enclosed as a cocktail lounge. A new canopy was installed over the entrance and the black Vitrolite and Prince of Wales motif sadly removed.

From 1937, the new hotel attracted a homosexual clientele. The east section of

the public bar has had gay drinkers since it opened. Some present customers

have been drinking there for over 40 years, yet it is rarely mentioned in the

gay press, or in gay guides. It is the oldest gay bar in

The Prince of Wales has always had a gay bar as long as I can remember. You couldn’t move there on Friday and Saturday nights. The bar next to the gay one in the Prince of Wales was the straightest roughest bar in town and you’d have the one next to it just full of people screaming and hooting and having a good time, never any problems at the POW

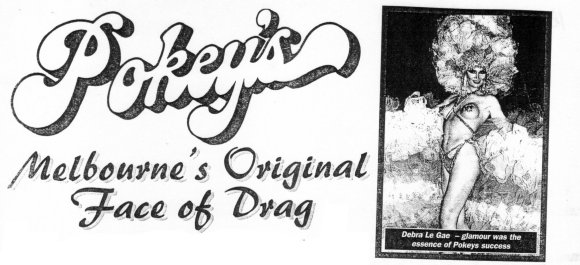

In 1977, the gay dances organised by Jan Hillier

since the late 1960s, migrating to various venues across

The shows included spectacular and most professional drag cabaret performances

starring showgirls Renée Scott, Terri Tinsel, Debra La Gae,

Michelle Tozer, Wanda Jackson and Doug Lucas: ‘the

Pokey’s original dreamgirls,’

in shows such as ‘Women of the Eighties,’ and songs such as ‘Its not where you

start, its where you finish,’ ‘You’re my world’ and ‘I believe in dreams’. Doug

explained that they would apply for one late license each month, which meant you

could trade until

Mischa

Merz, who rented for $25 a week in

...my nights...punctuated by the sound of men in high heels going to and from the Prince of Wales, the slamming of doors and the squeal of tyres...sirens, screams, shouting and the sound of breaking glass almost every night.. Like scenes from Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver on a loop. Neon signs, odd characters, men dressed as women, bad people offering you a good time for a price. Friends and family were a little concerned. Some were too frightened even to visit. It was my idea of utopia.

Since 1996, the Gay Pride March has

been held each year in

The Band Room and the ground floor corner piano bar also became major pub music

venues for

In 1996, the hotel’s freehold was sold to John and Frank Van

Haandel, the proprietors of the most successful

Stokehouse Restaurant in

In 1998, when redevelopment of the Prince was announced, a group of St Kilda film makers were determined to immortalise the apocalyptic moment on celluloid. Film director Lawrence Johnson described the atmosphere they sought to record: ‘There is a sense of violence, of danger, around this area and especially around this pub and its bars... out-of-towners visited St Kilda at the weekend because of its notorious reputation and the pub because of its social history... there were a lot of stories associated with this bar like when women weren’t allowed in here and they used to pass drinks at through the windows’. Last Drinks was completed in 1998, directed by Kate Morrow. The groundswell change-of-life that has infused Fitzroy Street, Acland Street and parts of Carlisle and Inkerman Streets over the past decade, began at Caffé Maximus (7), designed by architect Alan Powell (13) in 1988. This has reached its apogee in the most recent incarnation at the Prince, again by Powell, completed over 1998-99, as it pitches its play to where it all began in 1937, when a beer-house was reclaimed for the smart set.

McIntyre’s Streamlined exterior has been largely

recovered, including the classy black-tiled piers. The rougher bars of the

ground level and the Band Room have been subtly consolidated.

Dramatic gesture, illusion and clever design intervention,

sweep patrons up a dramatic stair to the first floor. There is a slender

sleek cocktail bar; a vaporous restaurant, Circa at

the Prince and an internal courtyard to ventilate the boutique hotel rooms on

the upper floors. In October 1998 it won

In 2001, the Health Spa at the Prince was designed by the innovative architects,

Wood Marsh Pty Ltd. Their previous St Kilda design is the exciting public

toilets in the St Kilda Botanical Gardens,

Cilento,

Jeane-Marie. ‘The Decorated Prince’.

McCulloch, Alan. Encyclopedia of Australian Art.

McDonald, Grant and Street, Janet.

Director: Kate Morrow. Last Drinks. A Film

About a

Masterton, Andrew. ‘Wails for the Prince.’

The Age.

Merz, Mischa. ‘St

Kilda’s battle of the bland’. Herald

Miller, Harry Tatlock (Ed) and

Robertson,

Natural Trust of

Oral

history interview with Doug Lucas by Graham Carberry

and Mark Riley for the Australian Lesbian and Gay

Archives,

‘Pokey’s.

‘Prince of Wales Health Spa. Wood Marsh Pty.Ltd. Architecture’. Architect. June 2002. Pp 14 & 48.

“Prince of Wales Hotel, St Kilda,

Rollo, Joe. ‘Prince goes showbiz’ The Age.

Slee, Amruta. ‘The Prince’.

Sunday Age.

“The Hotel Dresses Up... “The Modern Store. February, 1937. pp 11-14, 45 & 46. 48, 50, 61 & 62. Upton,

Gillian. The George: St Kilda Life and Times.

Wilson,

Catherine. ‘Pokeys Revisited’. MCV.

Wilson,

Catherine. ‘Doug’s World’. MCV.

Whiffen, Scott. “‘Prince’ to be

immortalised”. Port Philip Leader.

|

||

|

St Kilda Historical Society Inc. © 2005 |