|

|

||

|

Home | Introduction | Contents| Feedback | Map | Sources | Glossary |

||

|

9

Figsby & Fareham

Figsby

and

Figsby

& Fareham,

The important early journalist and novelist

Marcus Clarke (1846-81), lived at

Albert Tucker (1914-99) and his wife Joy

Hester (1920-60) were two of

Housing was scarce during the war, so in early 1945 they gladly pounced on a spacious first floor north-facing front room, with a kitchen adjoining. (This room is now a bathroom). Here at Figsby, they both worked, preferring the southern light and shared a ‘scruffy’ bathroom with other tenants. In this single room, they slept, lived and painted. Here they produced commercial art and the cover of the 1944 (Images of Modern Evil) issue of the famous periodical Angry Penguins.

It was while they were here, that their son,

Sweeney Hallam Tucker was born on

We all gotta do what we

gotta do

But Elliot depicts a threatening world of

spiritual terror and exposes a man’s horror at his capacity for violence.

There’s a savage, almost sadistic love duet between Sweeney and Doris: ‘Birth

and copulation and death. / That’s all, that’s all, that’s all, that’s all.

/ Birth and copulation and death.’ But who was the

obsessed Sweeney? Clearly these images influenced Tucker’s work, a morally

distorting lens on wartime St Kilda, like those in Nolan’s

On the balcony, Bert constructed a playpen for their Sweeney. Twenty years later, I knew Sweeney Reed (1944-79) as the glamorous and charismatic entrepreneur of Strines’ Gallery, 130 Faraday Street, Carlton, long after at the age of two, he was taken to live with John and Sunday Reed in their artistic circle at Heide in Bulleen and who formally adopted him at the age of five (17). Here he was still living. Both Strines and Heide are still repositories of art: Strines, its exciting architecture now somewhat bowdlerised, is now Bridget McDonnell Gallery and Heide, much expanded as the Museum of Modern Art at 7 Templestowe Road. After the Reeds moved to their new house next door to Heide, Sweeney occupied their former home. Both are now open to the public as Heide I and II. Hester had grown up in Elwood, attended St Michael’s Church of England Grammar School and savoured St Kilda’s increasingly open beach culture: for Hester, living in St Kilda was like coming home. Tucker, the puritan, was horrified by the sexual, steamy street life of wartime St Kilda. In his novel, My Brother Jack, George Johnston describes the unravelling of inhibitions in the 1920s, which was only heightened during the war: Beyond our neat hedged perimeters, the world suddenly seemed transformed into a jungle of iniquities, of violence, of sex, flaunted revolt, and alarming uncertainties. The newspapers reprimanded in editorials the wayward follies and excesses of the young, quoted hair-raising legal reports of teen-age girls who carried contraceptives in their handbags, spluttered about ‘companionate marriage’, lifted their circulations with shocking stories of scandalous goings-on in parked coupés and sedans , and screamed for the burning of books. Along St Kilda Esplanade and in the open parks, policemen and Peeping Toms prowled with torches at the ready to catch flaming youth in the very act of burning.

After painting the masterly, abstracted

Sun Bathers and the leering Bride, both in 1944, Tucker returned to

his moralistic and iconic Images of Modern Evil series. Janine Burke,

his biographer, feels the seven images he completed at

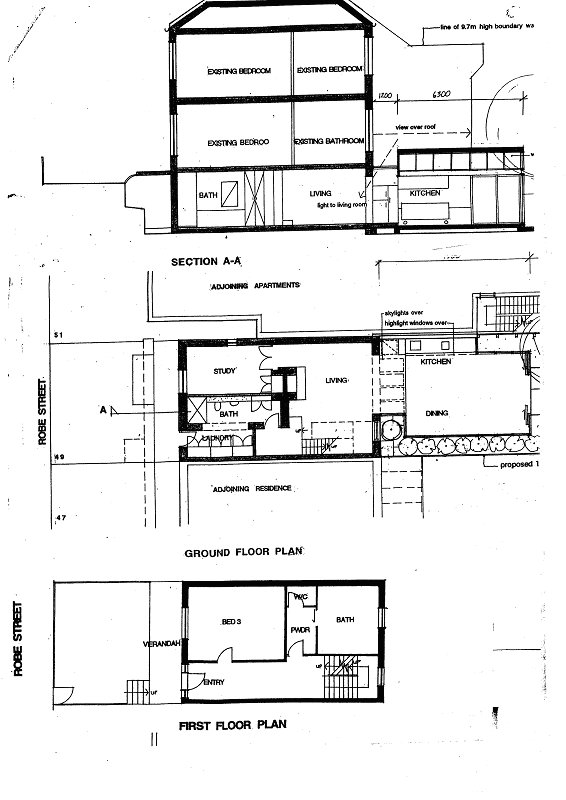

Plan view of Figsby & Fareham: Tucker and Hester occupied first floor

Tucker’s photographs of

If Tucker’s images painted at

Both Hester and Tucker were open to

experiences of the occult. One night, in bed reading they

were visited by the loud crash and rushing wind of a poltergeist. They

stared at each other paralysed with fear. Poltergeist is German for ‘noise

ghost’ (or ‘guest’). Ghosts, Burke explains, are said to be spirits of the

dead, bound to the place they haunt by anguish. Hester and Tucker both

wondered if

Sidney Nolan, having grown up in

As a dealer at Sweeney Reed Galleries,

Night Image,

No 13 in Tucker’s Images of Modern Evil series, depicts

These two polychromatic brick terraces are

unusual in

In the late 1970s, Albert Tucker decided to

return to live in St Kilda. He bought a large single-storied Victorian

terrace at

About 1980, after probably 40 years as boarding houses, the two houses were renovated by Urban Spaces Pty. Ltd, architects and builders, of which a couple of years later I became a director. Then the rear balconies were removed to capture more south light.

After two years overseas, following

completion of her earlier biography of Hester in 1985, Burke also decided to

return to live in St Kilda. With supreme irony, and perhaps some little

effect on Tucker, now remarried, Burke found a flat in Mimosa, a large 1920s

block in

References

Albert

Tucker. (Images of Modern Evil).

Night Image. No 13 and Night Image. No.19.

1945.

Oil-Damar varnish on plywood.

(National Gallery of

Allom Lovell

& Associates.

Young & Jackson’s Hotel.

Conservation Management Plan.

Australian Heritage Commission. Register of the National Estate. Burke, Janine. Australian Gothic. A Life of Albert Tucker. Knopf. Milsons Point, NSW . pp 259, 261, 262, 266-68, 278, 335, 417 & 419.

Burke,

Janine. Australian Women Artists 1840-1940.

Greenhouse.

Burke,

Janine. Joy Hester .

Greenhouse Publications.

Burke,

Janine. The Eye of the Beholder.

Albert Tucker’s Photographs.

Darian-Smith,

Kate. On the Home Front.

de

Serville, Paul. Pounds and

Pedigrees. The Upper Class in

Gelatly,

Kelly. Leave No Space for Yearning. The Art of Joy

Hester.

Gordon,

Lyndall. Elliot’s New Life.

Noonday.

Hart,

Deborah. Joy Hester and Friends.

National Gallery of

Joy Hester.

A Frightened Woman.

National Gallery of

Johnston,

George. My Brother Jack. .

Collins.

Lynn,

Elwyn. Sidney Nolan - Australian.

Bay Books.

National

Trust of

Robertson, E.

Graeme. Ornamental Cast Iron in

Robertson, E.

Graeme., Robertson, Joan. Cast Iron Decoration: A World Survey.

Sidney Nolan. Robe Street, St Kilda. 1945. (Deutscher-Menzies). Sidney Nolan. Moon Boy. 1939. Enamel on canvas, on hardboard. 1939. (Australian National Gallery).

Sidney Nolan.

Moon Boy. 1945. (

Slater, Dr

John. Fax to Richard Peterson dated

Stanhope,

Zara.

Moments of Mind: The Sweeney Reed Collection.

|

||

|

St Kilda Historical Society Inc. © 2005 |